After you invited me to the Biennale di Ceramica (Ceramics Biennale) in 2003, I thought about the direction that my work might take. Given my origins and the direction of the Biennale itself, I thought it was important to turn my attention to the local area. There were many reasons why I chose coal as a ‘model’ – formal, environmental and ‘sentimental’. The house in which I was born and where I grew up in Vado Ligure was a few hundred metres from the factory where I collected coal fragments to make the moulds for my ceramic pieces. The train passed a few metres from my house, taking the coal to wherever it was going. Lumps of coal often fell off the wagons and collecting them earned my childhood friends and me a little bit of money.

Coal was still very important to the economy and as fuel at the time (late ‘60s and ‘70s) both in our little community and on a worldwide. Something that is important to remember is that at the time no one would ever have imagined the devastating effects this could have on our lives and our health. Air affected by sulphur emissions dried out the trees, great architecture was worryingly blackened, streams were imprisoned in “beds” of concrete whose fetid vapours created permanent rainbows. Welcome to chaos! Inevitably, this extreme landscape became my playground. One of my favourite paintings by my father Achille (1920- 1962), a Realism artist, is an oil painting where you can see the outline and towers of the coke plant, the subject of the photo-essay that I’ll use for the new exhibition at the Ceramics Museum.

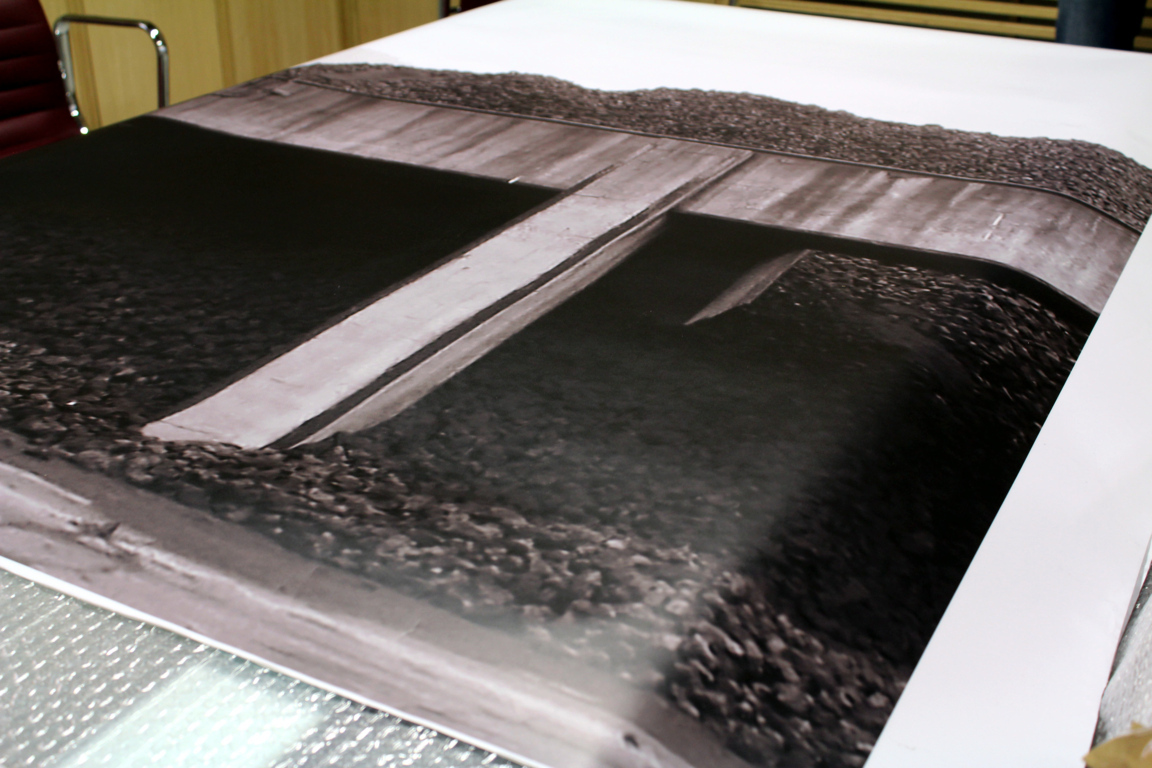

The giant poster of the photo of the coke plant that will be part of the new setting of the work Carbone by Vincenzo Cabiati

My relationship with ceramics – like that with coal – began in my childhood. As I said, my father was an artist. Ceramic and sculpture were very important to his work. In the garden of our house in Vado Ligure he had a gas oven built (produced by the coke plant) to fire the clay. It was made by the technicians who built them in the village factories to fire clay. I find a privilege to use clay and sculpture to relate to everything around me. Fragility becomes an identity. Coal is an element, a powerful symbol which characterizes the industrial revolution of the 20th century. The dynamics of its production changed my life and my environment for several years. Such close contact with an environment that is so compromised by pollution makes any kind of objective judgement impossible. Paradoxically, the gasses produced during the process of working the coal were used to ‘bake’ both the sculpture and food. This has created ties of dependency, necessity and affection.

I am very aware of these events which seem astounding and completely unthinkable for someone who lived in this area until the early ’80s. Of course, one could try to explore the ideas and connections within the problems created by the materials in relation to the environment and those who live in it. However, I don’t think it is appropriate to give an opinion here on scientifically complex ideas that have already been discussed a great deal in this context. Recent history, including the court cases, are difficult to understand in full. The content and symbols in my work have been enriched in a way tha I could not have envisaged. All this annihilates time, and that’s something that I love.

Vincenzo Cabiati, originally from Vado Ligure, was born into a family of artists and was heavily influenced by his father Achille’s work, whose formative years took place in the golden years of Realism during the 50s. Having learnt his craft in his father’s studio, at the end of the 80s he left Liguria for Milan, where he held his first exhibition “Femminea” at Galleria Giò Marconi, where he met the group of artists of Via Lazzaro Palazzi. Cabiati’s works are rife with influences from cinema, architecture and art, intertwining and continuously finding new sources of inspiration through the use of important elements and different methods. His aim is to extrapolate the most important elements of reality, contributing to their renewed poetic and emotional value. Cabiati has a strong bond with polychrome ceramics, which came about during his childhood thanks to his father Achille, and today is his preferred medium of expression.

Take a look to the other interviews